Written with love, shared with joy.

The Journey of Ancient Chinese Vertical Writing

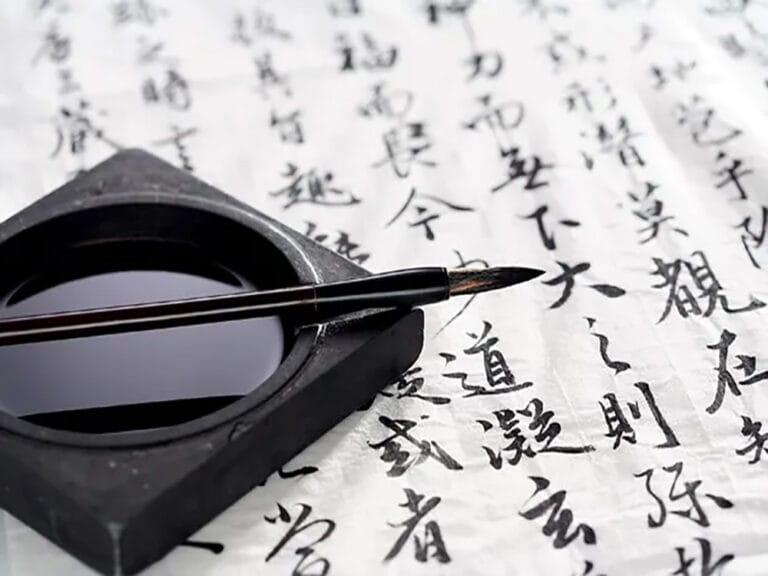

Ancient Chinese vertical writing unfolds like midnight blossoms in the hush of a scholar’s studio, where candlelight licks at silk scrolls and ink pools like liquid shadow. Here, characters fall in sacred procession—vertical, right to left—as if the heavens themselves dictated their descent. A brush trembles, breathing life into strokes that carry the weight of oracle bones and imperial edicts. To read these Chinese vertical scripts is not merely to scan words, but to trace the spine of a civilization: a rhythm of eyes climbing downward, hands unrolling time, and souls tethered to the divine.

The Oracle’s Secret

In the shadow of the Shang dynasty’s temples, a diviner kneels, clutching a turtle shell. His blade etches symbols into the bone—cracks and lines that whisper to the gods. These oracle bone inscriptions (甲骨文), China’s earliest known writing, flow in vertical columns. Each stroke is a prayer, carved downward to mirror the descent of divine will.

Why vertical? The answer lies in the diviner’s hands. Right-handed and ritual-bound, he carves from top to bottom, letting the blade follow the bone’s natural grain. Columns cluster from right to left, like soldiers marching toward the unknown. Even then, writing was a dance between human intent and the materials that confined it.

Bamboo’s Whisper

Centuries later, a scribe in the Warring States period binds bamboo slips with hemp string. Each strip, no wider than a finger, bears a column of ink. To read his chronicle of battles and harvests, one unrolls the scroll with the left hand, guiding the right hand’s brush. The slips rustle like leaves, their vertical lines echoing bamboo’s own growth—upward yet segmented, rigid yet alive.

The Guodian Slips: Discovered in a tomb in Hubei, these 300 BCE bamboo strips hold fragments of the Tao Te Ching. Here, Laozi’s words — “The Tao that can be spoken is not the eternal Tao” — wind downward, each character a step on a spiritual staircase. The scribe’s ink has faded, but the vertical flow remains, a river of thought frozen in time.

Silk and the Scholar’s Pride

In a Han dynasty palace, a concubine gifts her lover a silk scroll. Its surface glimmers, softer than moonlight, bearing a poem by Qu Yuan. Unlike bamboo’s austerity, silk allows curves and flourishes—yet the characters still stand tall, vertical sentinels guarding the heart’s secrets.

Silk was luxury; paper would be revolution.

When Cai Lun presented his paper to Emperor He in 105 CE, he little knew he’d democratize knowledge. Yet even on this humble medium, tradition held sway. Scrolls grew longer, but readers still traced columns from right to left, their fingers brushing centuries of habit.

The Monk’s Legacy

In a Dunhuang cave, 9th-century monk Hongbian kneels before a sutra. The Diamond Sutra, printed with woodblocks, proclaims: “All conditioned things are like dreams.” Its words march vertically, a bridge between earth and nirvana. When British explorer Aurel Stein uncovers this text millennia later, he marvels not just at its age, but at its form—a vertical pilgrimage of devotion.

The Poet’s Lament

Li Qingzhao, Song dynasty’s greatest poetess, pours wine and grief onto paper. Her elegy for a lost husband flows in vertical lines, each character a tear. “I search, yet find nothing,” she writes, the brushstrokes heavy as rain. Butterfly-bound books, their pages folded like wings, preserve her verses. To flip them right-to-left is to wander her sorrow’s labyrinth.

Winds of Change

The 19th century arrives with steamships and missionaries. Western books—horizontal, left-to-right—clash with scrolls in Shanghai’s ports. Reformers like Liang Qichao argue: To modernize, we must write like the world.

By 1955, Mao’s decree seals the shift. Horizontal text sweeps China, pragmatic and uniform. Yet in Taipei’s night markets, calligraphers still paint shop signs vertically, defiance and nostalgia in every stroke.

The Vertical Soul

Today, vertical writing survives where beauty trumps utility.

On TikTok, a teen inks classical poetry vertically, her phone tilted sideways. “It just feels right,” she says.

And in Kyoto, a Shinto priest hangs an ema plaque. His prayer, brushed downward, rises to the gods like smoke.

Ancient China’s reading order was never mere convention. It was the sway of bamboo in wind, the fall of ink from brush, the unbroken thread tying earth to heaven. To read vertically is to move through time — a slow, sacred dance that modernity has streamlined but not erased.