Written with love, shared with joy.

The Timeless Beauty of Classical Chinese Literature

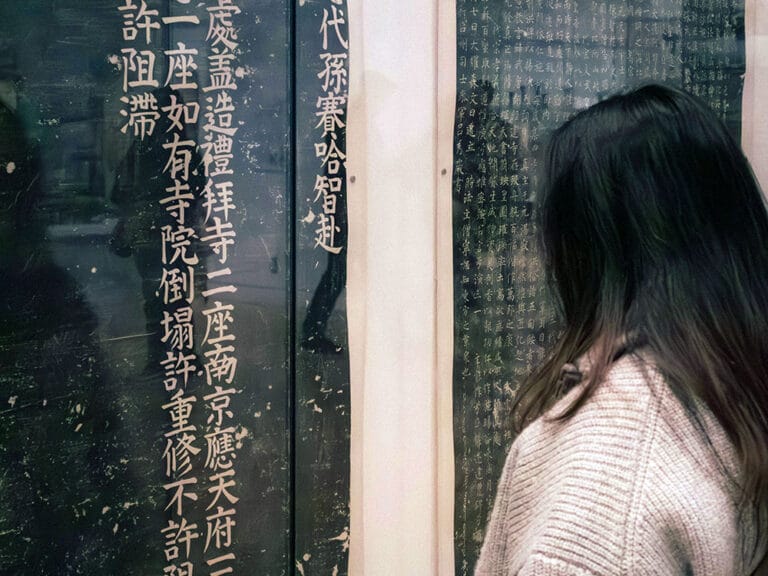

As you can see, most of my calligraphy works are written with classical Chinese literature. These elegant brushstrokes are not just art – they’re windows into a rich literary tradition that has shaped China’s cultural soul for millennia. For Western readers curious about the essence of classical Chinese literature, Tang poetry (唐诗) and Song lyrics (宋词) are the perfect starting points. These two forms represent the pinnacle of Chinese poetic expression, blending philosophy, nature, and human emotion into concise, evocative verses. Let’s explore their history, themes, and enduring legacy.

Why Classical Chinese Literature Matters

It is more than ancient texts—it’s a bridge to understanding China’s values, aesthetics, and worldview. Unlike Western epics or novels, traditional Chinese poetry emphasizes brevity and suggestion. A single line of Tang poetry or a stanza of Song lyrics can convey profound emotions, vivid landscapes, or timeless truths. For modern readers, these works offer a meditative escape and a glimpse into a society that revered harmony with nature, moral integrity, and the beauty of simplicity.

The Golden Age of Tang Poetry (618–907 CE)

The Tang Dynasty is often called China’s “Golden Age,” a time of political stability, cultural exchange, and artistic innovation. Poetry became a universal language, practiced by emperors, scholars, soldiers, and even monks. Over 50,000 Tang poems survive today, written by more than 2,000 poets.

Key Features of Tang Poetry

- Structure and Form: Most Tang poems follow strict tonal patterns and rhyme schemes. The jueju (绝句, quatrain) and lüshi (律诗, regulated verse) are the most iconic forms, balancing symmetry and spontaneity.

- Themes: Nature, friendship, solitude, and the passage of time dominate Tang poetry. Unlike Western romanticism, Tang poets sought to capture the essence of a moment rather than narrate a story.

- Famous Poets:

- Li Bai (李白): Known as the “Immortal Poet,” Li Bai’s works celebrate freedom, wine, and the sublime power of nature. His poem Quiet Night Thoughts (《静夜思》) is memorized by every Chinese kid:

Before my bed, the moonlight glows,

Like frost upon the ground.

I lift my head to gaze at the moon,

Then bow, homesickness unbound.- Du Fu (杜甫): The “Poet Sage,” Du Fu wrote with moral depth and empathy, reflecting on war and human suffering. His Spring View (《春望》) captures the turmoil of rebellion:

The nation shattered, hills and streams remain.

Spring in the city: grasses grow unchecked.

Even flowers shed tears of grief;

Birds startle, parting from loved ones.- Wang Wei (王维): A painter-poet, Wang Wei fused Buddhism with nature imagery. His Deer Enclosure (《鹿柴》) epitomizes tranquility:

Empty mountain, no one in sight,

Yet voices echo through the woods.

Sunlight pierces the deep green moss,

Reflecting onto the azure rocks.Why Tang Poetry Resonates Today

Tang poems distill universal emotions into minimalist language. Their focus on transience – cherishing a moonlit night or mourning a fallen blossom – mirrors modern mindfulness practices. For Western readers, they offer a fresh perspective on how to find meaning in fleeting moments.

Song Lyrics (Ci): The Music of Emotions (960–1279 CE)

If Tang poetry is a polished gem, Song lyrics (词) are a flowing river. Emerging during the Song Dynasty, ci were originally lyrics written to fit existing musical tunes. Unlike Tang poems’ rigid structures, ci vary in line length and tone, allowing for greater emotional range.

The Rise of Ci Poetry

The Song Dynasty saw urbanization, technological advances (like printing), and a growing middle class. Ci became popular in teahouses and courtly banquets, blending scholarly refinement with folk sensibilities.

Hallmarks of Song Lyrics

- Musicality: Each ci follows a cípái (词牌), a fixed tonal pattern tied to a melody. Titles like The Moon Over the West River (《西江月》) evoke the mood of the tune.

- Intimacy and Ambiguity: Song lyrics often explore love, longing, and personal sorrow. The language is more colloquial than Tang poetry, yet layered with metaphor.

- Iconic Poets:

- Su Shi (苏轼): A polymath and statesman, Su Shi (also known as Su Dongpo) expanded ci beyond romance into philosophy and social critique. His Prelude to the Melody of Water (《水调歌头》) reflects on life’s imperfections:

When will the moon be clear and bright?

Raising my wine, I ask the azure sky.

People have sorrow and joy, parting and reunion;

The moon has clouds and sun, wax and wane.

Since ancient times, nothing stays perfect,

May we live long, sharing the moon’s beauty, miles apart.- Li Qingzhao (李清照): China’s greatest female poet, Li Qingzhao wrote haunting ci about love and loss. Her Slow, Slow Song (《声声慢》) begins:

Seeking, seeking, searching, searching,

So cold, so clear,

Dreary, dismal, desolate, distressed…

How could one word “sorrow” capture this?- Xin Qiji (辛弃疾): A military leader turned poet, Xin Qiji infused ci with patriotic fervor. His Green Jade Table (《青玉案》) contrasts festive scenes with inner loneliness:

A thousand blossoms light the night,

Once more, the east wind blooms the stars.

Precious horses carve perfumed roads,

Music swirls, moonlight flows,

Dragons dance till dawn.

Yet midst the crowd,

I search for her,

Turning back,

There she stands,

Where lanterns dim.Song Ci’s Modern Appeal

Song lyrics’ emotional intensity and melodic flexibility feel surprisingly contemporary. Their themes of love and existential doubt resonate with global audiences, while their ambiguity invites personal interpretation—much like modern songwriting.

How to Appreciate Classical Chinese Literature

For Western readers, diving into classical Chinese literature can seem daunting. Here’s a beginner-friendly guide:

- Focus on Imagery: Chinese poetry relies on nature symbols. Pine trees signify resilience, cranes represent longevity, and moonlight often evokes homesickness.

- Embrace Paradox: Many poems balance joy and sorrow, movement and stillness. Li Bai’s exuberant drinking songs mask a fear of mortality; Li Qingzhao’s love poems mourn absence.

- Read Aloud: Even in translation, the rhythm and alliteration of Tang poems or the cadence of Song lyrics carry emotional weight.

- Explore Translations: Compare versions by translators like Arthur Waley, Burton Watson, or Stephen Owen to find one that speaks to you.

Classical Chinese Literature in the Modern World

Tang and Song poetry remain deeply ingrained in Chinese culture and even daily life. They’re quoted in political speeches, adapted into pop songs, and even inspire social media trends. For instance, Du Fu’s verses recently went viral on Youtube, with BBC reporter praising his “relatable” angst. Meanwhile, calligraphers like me keep the tradition alive by inking these timeless words onto paper.

Conclusion: A Living Legacy

Classical Chinese literature isn’t confined to history books – it’s a living art form that continues to inspire. Whether you’re drawn to Li Bai’s free-spirited odes or Li Qingzhao’s poignant laments, Tang poetry and Song lyrics offer a mirror to our shared humanity. As you explore these works, remember: each character brushed in ink carries a thousand years of wisdom, waiting to be discovered.